NEWS & UPDATES

For GPs – Common healthcare interactions and Cerebral Palsy

14 Nov 2025

Do you have a new GP, are you switching clinics or dealing with a new nurse or specialist? Are you bringing your baby to the GP for the first time since their Cerebral Palsy diagnosis?

This article has information for medical practitioners about caring for a patient who lives with CP. You can use the link to this article, or print out this PDF version, to share it with your medical practitioners.

By Amy Hogan

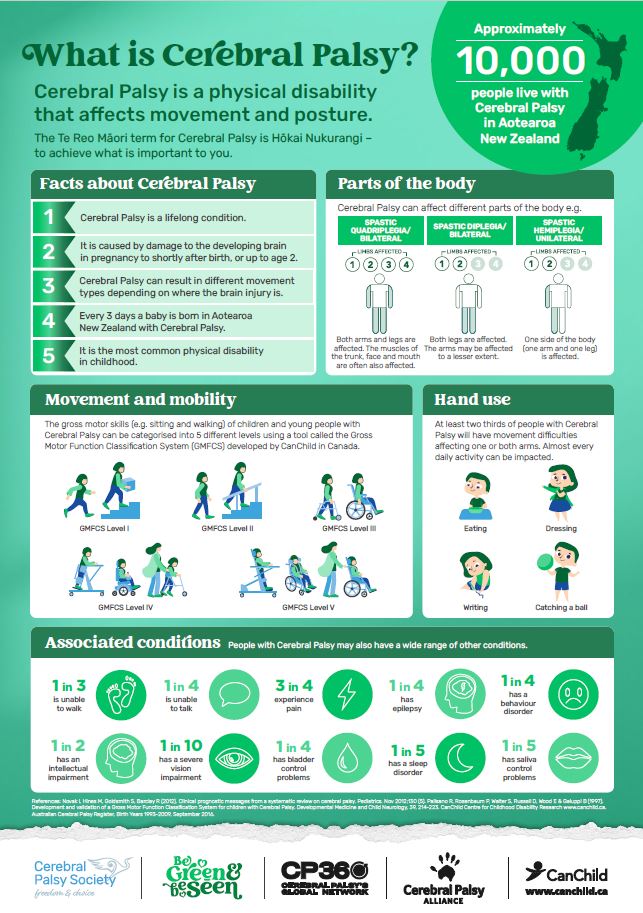

Every three days, a baby is born in Aotearoa New Zealand with Cerebral Palsy – Hōkai Nukurangi*.

Every three days, a baby is born in Aotearoa New Zealand with Cerebral Palsy – Hōkai Nukurangi*.

It’s a striking statistic for a condition that has a low profile.

Cerebral Palsy (CP) is the most common physical disability in childhood.

People with the neurological condition don’t grow out of it, so there are a large number of adults living with it.

It affects the movement, mobility, and posture of approximately 10,000 New Zealanders.

What is Cerebral Palsy?

CP is caused by damage to the developing brain during pregnancy, shortly after birth, or up to the age of two. It can result in different movement types and affect different parts of the body depending on where the brain injury is, and CP can present on a broad spectrum.

At least two-thirds of people with CP will have movement difficulties affecting one or both arms. Almost every daily activity – eating, writing, dressing – can be impacted.

The information listed below can appear daunting. However, there are many ways in which GPs can support people living with CP and make their daily experiences of their condition a little easier.

The science around CP and lifelong conditions is also evolving and producing a more sophisticated understanding of how to help individuals and their families. The picture may look different in the coming years with advancements in neonatal support, therapeutic interventions, and medication management.

- 1 in 3 is unable to walk

- 1 in 4 is unable to talk

- 3 in 4 experience pain

- 1 in 4 has epilepsy

- 1 in 4 has a behaviour disorder

- 1 in 2 has an intellectual impairment

- 1 in 10 has a severe vision impairment

- 1 in 4 has bladder control problems

- 1 in 5 has a sleep disorder

- 1 in 5 has saliva control problems

There’s more information in this fact sheet:

Making sense of disability and modern GP practice

People with CP, and disabled people more broadly, often experience multiple layers of healthcare interaction. For GPs, this may mean balancing complex, chronic, and interlinked needs within brief appointment times.

CP is lifelong and multidimensional — it may intersect with musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and mental health issues. In modern practice, recognising disability as part of a person’s context rather than as a problem to “fix” can make a significant difference.

Take time to ask your patient about fatigue, pain, or functional changes — these may not be the presenting complaint but can shape the person’s daily quality of life and self-management.

Making sense of diagnosis and documentation

GPs often hold the most comprehensive long-term record for disabled patients. However, many adults with CP were diagnosed in childhood and may not have accessible or up-to-date documentation in their current file.

When taking over care or updating records:

- Include the type and distribution of CP (if known)

- Note mobility aids, communication methods, and baseline pain levels

- Record associated conditions (e.g. epilepsy, reflux, spasticity, fatigue)

- Where information is unavailable, note this transparently rather than omitting it.

As with all patients, accurate and current documentation supports better continuity of care and helps when referrals or emergency visits occur. This can be particularly relevant to people with CP because there can frequently be multiple and complex handovers.

Common funding streams and referral requests

Many people with CP engage with multiple systems beyond primary care, including the Ministry of Health, Te Whatu Ora, and disability support funding (e.g.

Individualised Funding, Equipment and Modification Services, or ACC where relevant).

GPs are often asked to complete funding application , referral and management forms for their patients. Sometimes, there can be multiple forms depending on the time of year and funding deadlines.

- Vehicle or home modifications

- Mobility or communication equipment

- Specialist referrals (e.g. orthopaedics, rehabilitation, neurology)

- Medication management (e.g. spasticity medication, Botox).

Whenever possible, document functional impact rather than just diagnosis. For example: “Requires mobility aid for transfers” provides more context than “spastic diplegia”.

Different specialist requirements and obligations

People with CP, and disabled people more broadly, often experience multiple layers of healthcare interaction. They may have regular contact with physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dietitians, speech-language therapists, and orthopaedic or rehabilitation teams.

While GPs often coordinate these relationships, the referral processes and follow-ups can vary significantly across regions.

A proactive approach, such as confirming who holds ongoing responsibility for aspects of care, can reduce duplication and prevent gaps. For complex cases, multidisciplinary case conferences (in person or virtual) can save time and avoid fragmented communication between services.

Common experiences in healthcare interactions

People with CP frequently report both positive and negative experiences in primary care. Themes include:

- Access and environment: Wheelchair users may struggle to reach counters, transfer to exam tables, or fit in consultation spaces. Simple adjustments — such as a height-adjustable plinth or portable ramp — can dramatically improve access.

- Assumptions: Adults with CP are sometimes mistaken for paediatric patients or assumed to have cognitive impairment. Ask before assuming — and include the person directly in discussions, even if they use a support person.

- Pain and fatigue: Pain is common but often under-reported. Asking “How is your body feeling this week?” rather than “Are you in pain?” can elicit a more accurate picture.

- Communication: Allow extra time or written formats where speech or processing are affected. For some, a support person may interpret or relay information.

- Continuity: Seeing the same GP or nurse improves trust and helps capture subtle changes over time.

Practice accessibility

Accessibility starts before the appointment. Consider:

- Whether people using wheelchairs or mobility aids can safely enter and navigate all rooms

- Whether toilets, counters, and doorways are usable

- If parking and drop-off zones are close enough to allow safe access.

It is far easier — and more cost-effective — to build accessibility into practice design than to retrofit it later. However, accessibility can be a staged approach when redesigns, developments or moving premises are already underway.

Final thoughts

Caring for people with CP requires awareness, flexibility, and partnership. A small amount of extra planning can help create meaningful, inclusive care, benefitting not only the person with CP but also their whānau and the wider community.

The Cerebral Palsy Society of New Zealand is a charity that supports people living with CP and their whānau by providing information, advice and financial support. The Society also works in the advocacy and awareness space.

You can learn more and access resources at www.cerebralpalsy.org.nz.

For more information, contact the Cerebral Palsy Society’s Member Support Team:

- 0800 503 603

- cpsociety@cpsociety.org.nz

* Hōkai Nukurangi is the te reo Māori term for Cerebral Palsy and translates to achieving what is important to you.

* Amy Hogan is the Cerebral Palsy Society’s Researcher and Member Support Advisor.

* Amy Hogan is the Cerebral Palsy Society’s Researcher and Member Support Advisor.